How Does Gravity Shape Meaning?

From figure drawing to falling in love, gravity leaves its indelible imprint on the meaning of being human.

Gravity does not merely pull us down. It shapes the contours of our being.

What does gravity mean for us humans? Not as a textbook principle, but as a lived reality?

Meaning, as I take it, is not something we extract from the world like a mineral.

It is something that emerges — a dynamic structuring of experience, rooted in the body and shaped by our engagement with space, force, balance, and movement: the way we lean into a hill against the wind, the way we steady ourselves while carrying a sleeping child.

Meaning is not fixed. It flows from the way we live through our bodies, the way we perceive, act, and adapt.

Gravity is one of the most fundamental forces shaping that lived experience. It is not just a downward pull. It is a silent architect of posture, fatigue, rest, growth, and final surrender. Gravity bends not only our muscles and bones, but also our concepts, our metaphors, our ways of making sense.

When we speak of “being weighed down” by sorrow, or “standing tall” with pride, we are not reaching for distant symbols. We are drawing from the immediate reality of living in a body under the ceaseless pull of the Earth. Gravity, through our embodied interaction with it, becomes part of the scaffolding of meaning itself.

To see gravity clearly is to glimpse how meaning is made, not in the abstract, but in the press of flesh against ground, the sag of tired shoulders, the spring of a child leaping upward. It is in the way a body adapts, surrenders, or resists. It is, quite literally, in the shape of being.

Artists have long known this truth intuitively.

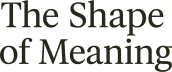

When learning to draw the human form, artists must learn not only anatomy, muscles, and bones, but also the effects of gravity. How flesh yields where it meets the ground. How breasts, stomachs, and limbs subtly flatten, elongate, or bunch depending on whether a model is lying down, sitting upright, or leaning to one side. The body is not static. It is a field of soft adjustments, a dialogue between inner structure and external pull.

In figure drawing, observing gravity’s work is what makes a sketch come alive. It allows an artist to suggest not just anatomy, but weight, rest, effort. A figure becomes convincing not because it is anatomically correct, but because it breathes the real physics of life: it is a body that belongs to the world.

Gravity reveals itself not just in art, but in everyday life.

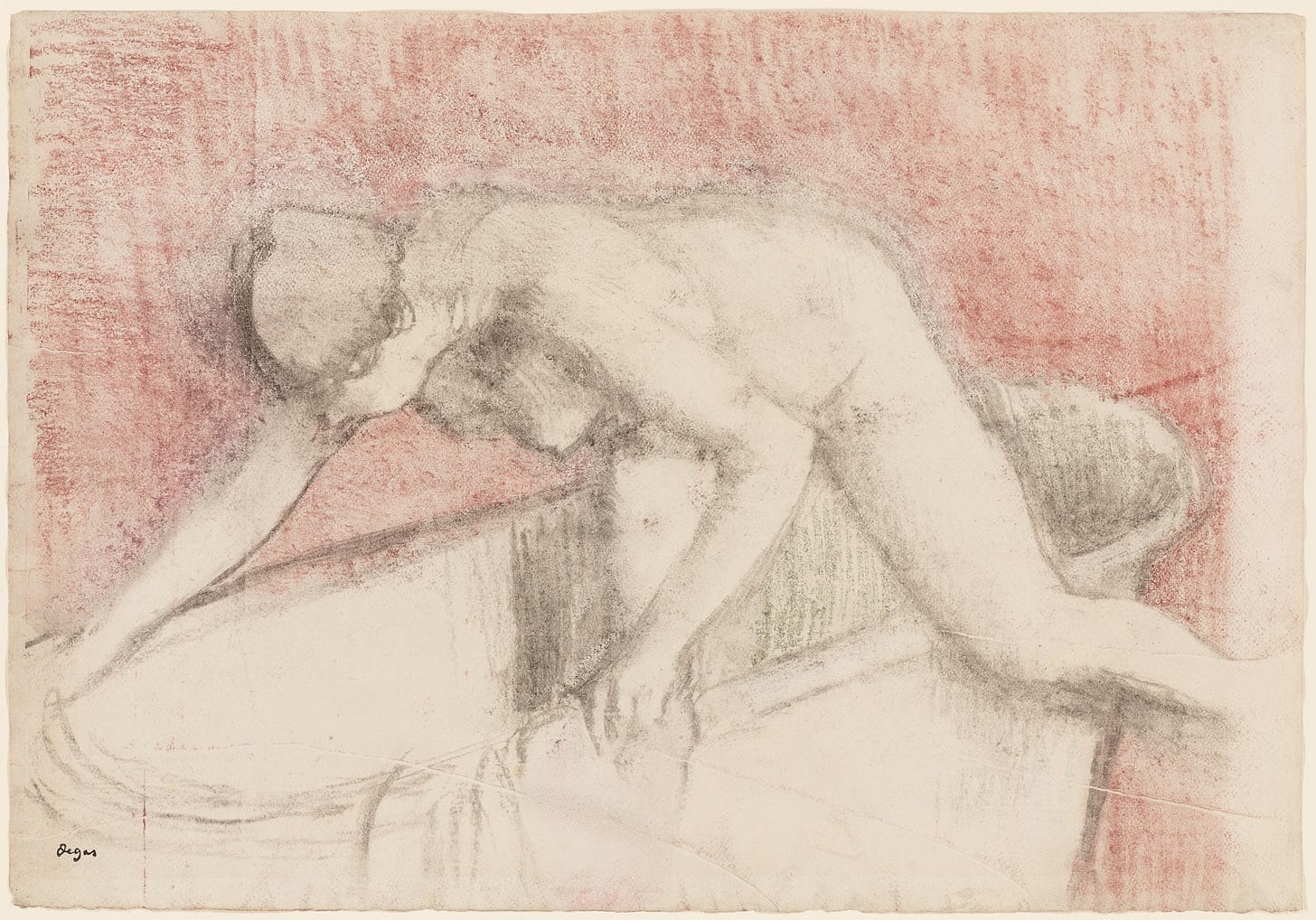

Watch an elderly man sit down slowly, carefully, as if negotiating a truce with gravity. Watch a child topple over with the careless joy of someone for whom falling is still a game. Watch a lover’s head find its way to a partner’s shoulder, pulled by a different kind of gravity—the desire to rest, to yield.

Gravity shapes how we move, how we tire, how we seek comfort — teaching us that living is always an act of balance between surrender and resistance. We are never free from gravity, but within its pull, we find the rhythms of effort, grace, exhaustion, and renewal.

And perhaps — in some quiet way — we find meaning.

If meaning, as we have seen it, is born from the structuring of experience, then gravity is one of its oldest architects.

It shapes not just bodies but also imaginations. It becomes the background rhythm of our metaphors: we speak of “falling” in love, of “lifting” our spirits, of “sinking” into despair. We associate “high” with achievement, “low” with defeat—not by arbitrary choice, but because we have lived those vertical movements in our muscles, our joints, our blood.

These metaphors are not ornaments added after the fact; they arise from the same bodily experience that gives rise to language itself. As George Lakoff and Mark Johnson showed in Metaphors We Live By1, much of our conceptual system is metaphorical in nature, grounded in the embodied realities of living creatures. Our narratives of struggle, triumph, collapse, and rest are not arbitrary inventions: they emerge from the deep structures of experience — shaped by forces like gravity — that silently scaffold meaning in our lives.

Even our myths remember: Icarus, flying too close to the sun, only to fall; Sisyphus, eternally pushing the stone upward. In every story of ascent and fall, the body’s ancient memory of gravity whispers underneath.

To live as a human being is to live within the pull of gravity—not merely pulled downward, but moving, resting, rising, and falling within its invisible field.

We do not escape it — and perhaps we would not want to. It is gravity that gives effort its nobility, rest its sweetness, and surrender its peace. It teaches us the shape of resilience, care, and grace under pressure.

Meaning, like form, is not forged in weightlessness. It arises from tension, contact, compression, and support. It arises from being held by an invisible hand.

In this way, gravity is not only a force we endure. It is a silent partner in our search for meaning, shaping us from the first breath to the last, rooting our stories in the simple, inescapable fact of being here — on Earth, in a body — falling and rising, again and again.

Artworks Featured

Large Reclining Figure, Henry Moore

The Bath, Edgar Degas

Pair of lovers, Ida Teichmann

Sisyphus (C. 1660 - 1665), Antonio Zanchi

Author’s Note

This post is part of an ongoing exploration of meaning through cinema, science, and the lived experience of being human. Here, I reflect on how meaning emerges from the hidden forces that shape the way we move, imagine, and make sense of the world.

If this reflection stirred anything in you — a memory, a movement, a story shaped by gravity — feel free to share in the comments.

In upcoming posts, I will continue tracing how hidden forces shape the ways we live, imagine, and find meaning.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.