Nineteen months into my drawing practice, I begin to notice something, not only about art, but about life itself.

The paper teaches as much as the pencil. The shadow teaches as much as the light.

This reflection on the self came to me while shading forms, tracing lines, and correcting mistakes. What follows is metaphorical. Like all metaphors, parts of it evoke what happens in real life, while others may be a stretch. But the stretch itself reveals something: how stress and shadow, in life and in art, shape the form of who we are becoming.

Core Shadows

An artist begins with the core shadow, the quiet heart of darkness that defines the form.

From there, the hand moves outward,

step by step,

never skipping the in-between tones.

Every value matters, even the ones you can’t yet see.

The self is drawn the same way. Stress leaves its core shadow: deep, central, shaping how light can fall. Around it, form shadows spread, soft gradations where strain and resilience meet. Cast shadows spill further, marking the ground of our days.

Work too fast,

and you flatten the subtle turns of the surface.

Ignore the faint transitions,

and the shape becomes rigid,

locked into its earliest marks.

Slow attention,

layer by layer,

is what keeps the form alive,

in graphite,

and in the self.

Busy Folds

Begin where the shadows are busiest.

Where edges meet and fold,

where the shape is jagged and restless.

There, the structure shows itself quickly,

not in the flat plains of calm,

but in the crowded topography of stress.

Every self has its core shadows, and around them, the mid-tones, those half-lit passages where strain blends into adaptation.

In quiet seasons, these changes are harder to see, like light diffused across a flat expanse.

But in the thick of things, in the tangled folds of trouble, the form of you is easier to read.

Anchor there.

Trace the halftones as they flow outward.

Then, when life smooths again,

you’ll still know the shape you carry.

Source of Light

Every form depends on its light.

Turn a fraction closer,

and the surface brightens.

Turn away,

and shadow falls.

Stress feels the same. The weight of it is not absolute. It depends on where you stand in relation to your source of meaning.

Close to the light,

even the hardest edges soften.

Far from it,

a small shift can darken everything.

Rembrandt knew

to deepen the shadows beyond what the eye first sees,

not to distort,

but to let the form be true.

So too with the self. Do not only copy what stress feels like in the moment. Shape it. Interpret it. Let the light you face reveal what the shadow conceals.

The Bigger Picture

It is easy to get lost in the small forms,

one shadowed fold,

one darkened corner,

one restless moment of strain.

But a life, like a drawing,

is not built from fragments alone.

Every stress must hang on a larger structure,

each mark flowing into the whole.

Step back.

See how the values distribute.

How the darker places balance the light.

How the jagged details soften

when seen as part of a bigger arc.

The self is not just the crisis of today or the worry of tomorrow. It is the movement that links them, the gesture that holds them together. Again and again, we must return to the larger shape, making small corrections, gently reconciling extremes, until the form feels alive.

Materials and Methods

Every drawing begins with its surface,

its tooth,

its grain.

Charcoal grips differently than graphite,

a soft pencil forgives

what a hard line makes permanent.

So it is with the self.

Stress does not press on us in the same way. Its mark depends on the body we inhabit, the histories we carry, the tools we’ve learned to hold.

There is no single right method.

Some need softness,

some precision.

Some must build tone slowly,

layer after layer,

until the form emerges.

The shadowed areas of life are forgiving.

The brightest planes demand more care.

And always, there is no prize for finishing first. The self, like the drawing, is shaped by the hand we bring, and by how patiently we let the marks settle into form.

Cycles of Learning

At first it feels impossible—

too many moving parts,

too many shadows to manage at once.

Like learning a new hand on the wheel,

the self stalls, jerks,

feels clumsy under pressure.

This awkwardness is not failure.

It is the sign of change.

Old habits breaking apart,

new ones not yet steady.

Then,

a breakthrough.

The form sharpens,

the self feels lighter, clearer,

as if stress has turned to strength.

But soon after comes the slide,

a setback, a falter.

Not the end of progress,

just the rhythm of it.

Over time,

these cycles carve a baseline.

Resilience becomes second nature,

like a hand shifting gears without thought.

And what emerges is not an ideal,

not some polished universal form,

but the particular self,

shaped by its own shadows,

its own light.

Closing Reflection

In Looking for Macbeth, my upcoming thesis film, I walk the same path as the drawings I practice.

Macbeth’s shadows harden him toward despair.

My own shadows, in these months of work, shape me toward form.

And so I see:

The self is always being drawn,

not once,

but continuously.

Macbeth’s story closes in collapse.

Mine remains unfinished,

still gathering shadow, still catching light,

still learning how a self is drawn into being.

If this reflection spoke to you, feel free to share it with someone who might need reminding that the self is always being drawn.

I’d also love to hear: where do you notice your own “shadows and halftones” shaping you? What practices help you see the bigger picture of your becoming?

Drawing Practice Sources

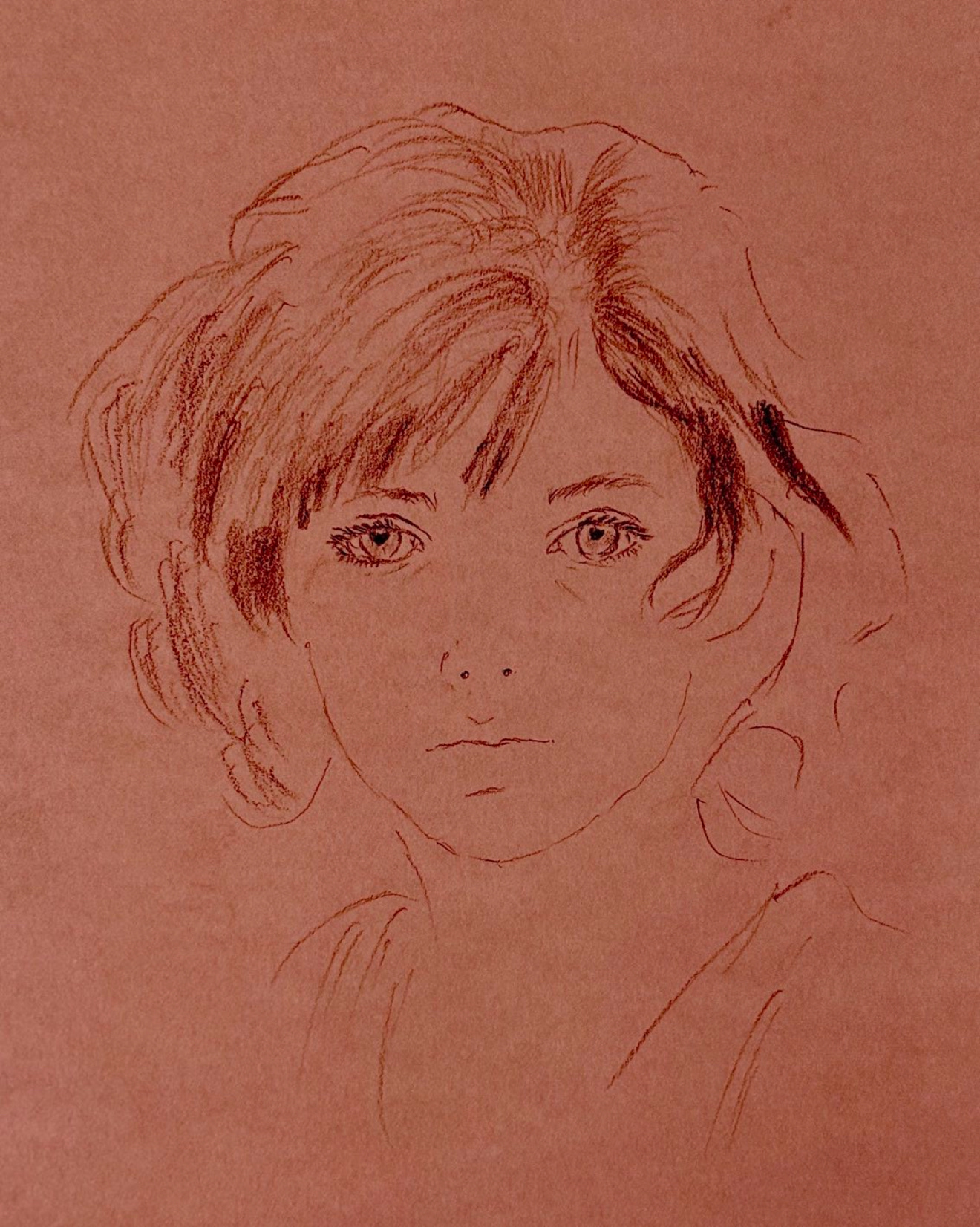

My drawing practice is organized around small daily challenges, often working from photographs for inspiration. Lately, I’ve been exploring portraits, and I’ve found the books by Miguel Àngel Molina particularly helpful, as they’re geared toward direct practice. They’re published by Posterlike (see Posterlike.com).

Juliette Aristides is also an inspiring teacher. See, for example, her Lessons in Classical Drawing: Essential Techniques from Inside the Atelier (2011, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York).